The so-called super trawler, the Margiris, which appeared in Australian waters a month ago is a doom-laden harbinger of things to come. These massive vessels have been slowly increasing in number, as a few large fishing companies look for larger profits from a dwindling fishery resource.

The so-called super trawler, the Margiris, which appeared in Australian waters a month ago is a doom-laden harbinger of things to come. These massive vessels have been slowly increasing in number, as a few large fishing companies look for larger profits from a dwindling fishery resource.

It was heartening to see the Aussies and a number of NGOs get up in arms over the arrival of the Margiris. Under mounting pressure, Labour thankfully cobbled together a temporary ban on the vessel, but in many ways this battle has just begun. And the reason for this is economics – pure and simple.

Seafish Tasmania’s plan was to use the Lithuanian-registered vessel to fish for their entire quota of Jack Mackerel and redbait, and in the process replace over 20 locally crewed vessels. This would see 20 Captain’s jobs disappear. And 20 First Mate jobs, then there are Deckhands and Engineers – all gone with the appearance of a single vessel. So the company will catch the same amount of target fish, but with many fewer employees. And fewer employees of course equal greater profits.

We have seen this shift happening already. The quota system tends to favour larger operations, but what made the Margiris different was the sheer jump in size.

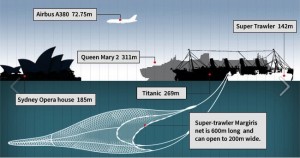

It is over double the length of the next biggest vessel to ever fish legally in Australian waters. Its impact on the fishing industry would be enormous. You cannot replace 20 local vessels overnight without it severely impacting the local economy.

These huge vessels are changing the entire face of the fishing industry. It is shifting from being based on labour, to being based on capital. And a capital industry favours not the small local Operator but rather, global corporations.

Conservation groups, and especially Greenpeace, have also been quick to label the Margiris an environmental disaster, and in many ways they are right. Larger vessels have greater issues with by-catch – that is non-target species that are bought aboard dead and discarded overboard. Small operators have less by-catch, and from what they do catch, much of it is able to be discarded overboard before it dies.

There is also the issue of localised depletion that is exacerbated by large vessels. They rapidly catch their fish within small areas, leading to zones where there are no fish at all. This includes protected seals and dolphin that get caught up in the giant trawl nets.

The Margiris then has seen opposition from two sides, normally often at loggerheads – conservation groups opposed to the environmental impact, and local fishermen who are seeing their livelihood threatened. And it has been heartening to see this happen. In many ways small fishing operators are conservationists. They want to see their fishery managed sustainably because that is their future livelihood. A Lithuanian registered, Dutch owned vessel crewed by people from goodness knows where has little interest in preserving local fish stocks – they’ll simply move onto the next country foolish enough to let them in.

Update: November 2012

The Federal Government has decided to impose a two-year ban on super trawlers, undermining plans by the operators of the Abel Tasman to begin commercial fishing.

http://www.abc.net.au/news/2012-11-19/supertrawler-decision/4380016. It’s believed the Tasmanian company that own the Margiris are fighting the ban in court…watch this space!